Can You (Safely) Dig It?

Photo: Roco Rescue

Construction

Trench collapses are preventable, but safety measures are often skipped

By Chris McGlynn

T

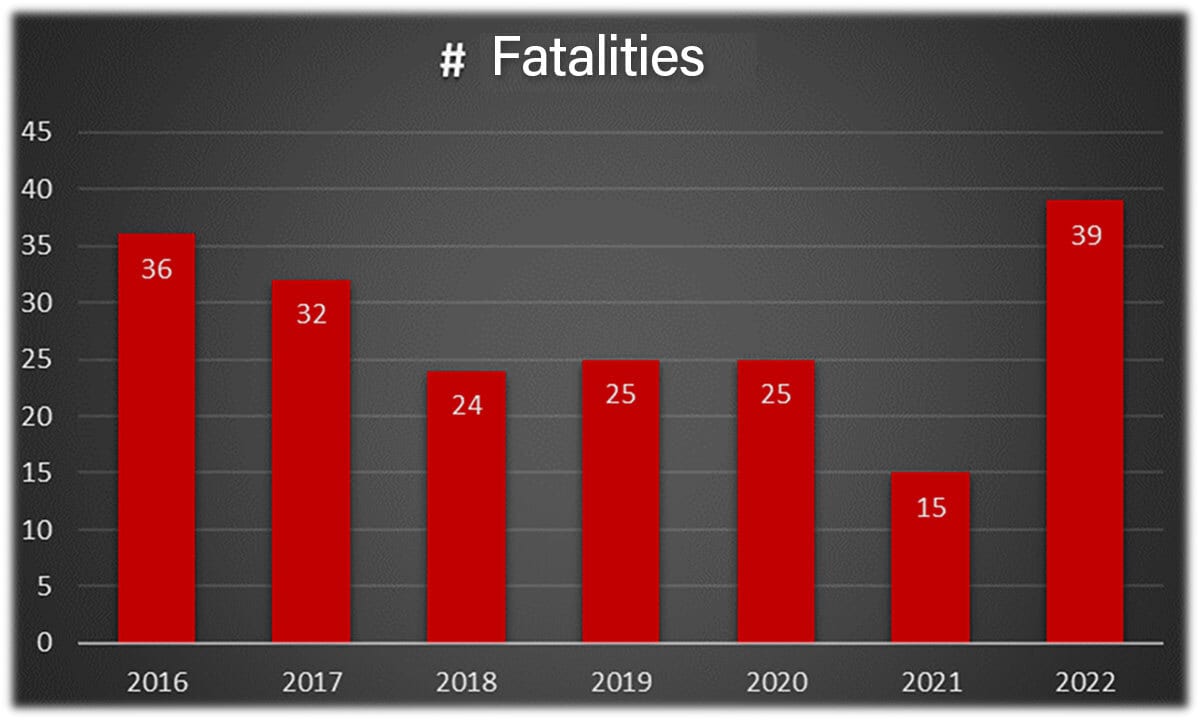

renching work remains one of construction's most lethal activities, yet its dangers are often underestimated. Each year, dozens of workers lose their lives in entirely preventable collapses. The statistics paint a sad picture: between 2003 and 2017, 373 workers died in trench-related incidents, averaging about 25 fatalities annually. More than 80% of these fatalities occurred in the construction industry. Even more alarming, 2022 saw a dramatic spike, with 39 deaths, more than double the previous year’s total. These aren’t abstract numbers; they represent parents, spouses, children, friends and colleagues who never returned home.

Chart: Roco Rescue

The Nature of Trenches

A trench, by OSHA’s definition, is a narrow excavation deeper than it is wide, with the bottom no broader than 15 feet. What makes trenches so dangerous is simple physics: soil is heavy, and unsupported 90-degree walls will collapse. A cubic yard of dirt weighs nearly 3,000 pounds, about as much as a midsize car. When a trench wall gives way, several cubic yards can bury a worker in seconds, leaving little chance for escape. It’s not a matter of if, but rather, at matter of when.

Consider the case of two workers in Jarrell, Texas, in June 2022. They were in a trench 23 feet deep but only 34 inches wide. Despite three unused trench boxes sitting on-site, no protective systems were in place. When the walls collapsed, the men had no chance. This tragedy demonstrates a harsh reality: trenches don’t usually give warnings. They fail suddenly, and when they do, the consequences are often fatal.

Cave-ins are the leading cause of trench fatalities, but they’re far from the only hazard. Workers face electrocution from struck utility lines, suffocation in oxygen-deficient atmospheres, and crushing injuries from falling equipment. In one horrific incident, a worker drowned when a ruptured water main flooded a trench with 4,000 gallons per minute.

Many of these deaths share common root causes: No protective systems and no competent person present. OSHA requires trenches deeper than 5 feet to have sloping, shoring, or shielding. Yet in 64% of fatal cave-ins, no such protection was used.

In 86% of fatalities, no trained individual was present to assess hazards. OSHA’s "competent person" should be viewed as more than just a title. This individual must have the training to spot hazards (like fissures in trench walls) and the authority to halt work immediately. Their presence and active participation on the jobsite is essential in reducing hazards and preventing injuries and fatalities.

Both indoor and outdoor temperatures can fluctuate, so necessary protections may change from day to day.

OSHA’s Lifesaving Rules

To combat these risks, OSHA mandates strict precautions under Subpart P (1926.650-652). Among the most critical are the following:

Protective Systems: For trenches 5+ feet deep, walls must be sloped, shored, or shielded. The exact angle depends on soil type — stable clay (Type A) can be cut steeper than loose sand (Type C), which requires gentler slopes.

Access and Escape: Workers in trenches 4+ feet deep must have a ladder or ramp within 25 feet. Utility Checks: Dialing 811 before digging helps locate underground lines, preventing deadly strikes.

Spoil Piles: Dirt excavated from trenches must be kept at least 2 feet back from the edge. Piling it too close adds dangerous weight.

Equipment Awareness: Heavy machinery operating near trenches can destabilize walls and shall be at least two feet from the edge of excavations.

Rescue Planning: If a collapse occurs, untrained bystanders rushing in often become victims themselves. Proper rescue teams with shoring equipment are essential.

Daily Inspections: A competent person must examine trenches before each shift and after any hazard-increasing event, like rain.

Conclusion

Trench fatalities are preventable, yet they persist because safety measures are skipped to save time or money. The solution isn’t just better training or stricter rules; it’s honestly a fundamental shift in mindset. Every trench death is a failure of planning, a failure of leadership, and above all, a failure to respect the lethal potential of an unstable hole in the ground.

The next time you see workers in a trench, ask: Are protective measures in place? Is there a way out? Is someone watching for dangerous conditions? Ultimately the question should be “Can you dig it… safely?”

Chris McGlynn is the Director of Safety and VPP Coordinator at Roco Rescue. He is a Certified Safety Professional (CSP), nationally registered paramedic, and experienced rescue technician specializing in confined space and rope rescue. Chris holds a Master’s degree in Occupational Safety and Health and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. at West Virginia University’s Statler College of Engineering & Mineral