Thought Leadership

Approach

Photo: Ridofranz / iStock / Getty Images Plus

A Proactive

Three questions every safety leader should ask amid regulatory uncertainty

By Scott DeBow

I

n a time of shifting regulatory landscapes and uncertain federal guidance, we’re left asking, “What now?” But this moment isn’t just a challenge for safety leaders; it offers a unique opportunity to lead from the front. Waiting passively for new rules and mandates can create a dangerous lull, and proactive organizations know that compliance alone doesn’t guarantee the business outcomes —including safety performance — we’re all seeking. Instead, safety thrives through clarity, curiosity and continuous improvement.

From evolving OSHA guidance to emerging state-level rules around heat exposure, mental health and ESG-linked safety standards, today’s safety environment is anything but static. We face uncertainty about regulations, workforce expectations, stakeholder scrutiny and the changing nature of the workforce itself. Navigating this climate requires more than compliance. It demands resilient systems, engaged teams and leaders who ask questions and stay on top of changing standards.

With that in mind, here are three questions every leader should ask amid the current regulatory uncertainty:

Is work happening the way we think it is?

The real world of work is dynamic. Conditions shift, tools change, production pressures increase, resources decrease, and workers adapt to it all. This adaptability is what makes workers so amazing: making small adjustments in and alongside their work environments and doing their very best to solve problems while keeping work moving. What we need to be acutely aware of is how this adaptability, while good and driven by the best intentions, can multiply risk significantly.

This question challenges us to test assumptions and explore the actual conditions on the ground and primes some excellent follow-up questions as an opportunity to learn directly from the workforce. Such as: Are there procedures or instructions you find dumb, dangerous or difficult?

Dumb: Where it is clear the work instruction in no way matches the actual requirement to accomplish the task, perhaps increasing risk, production time, etc.

Dangerous: Where following work procedures or instruction may actually increase risk, be unrealistic, or work is out of scope of training, resources or capabilities.

Difficult: Work instructions or procedures that make sense, but are difficult to follow because of language, lack of visuals and/or lack of resources, application or context.

It’s important to challenge the assumption that work is being performed the way we imagine it to be. This sheds light on the inherit bias and assumption that goes with, “Because I wrote a procedure, it’s therefore good.” Great leaders lead from humility and curiosity, and these types of questions steer both leaders and workers closer to the reality of how work is really being accomplished; associated risks; and most importantly, problem solving together.

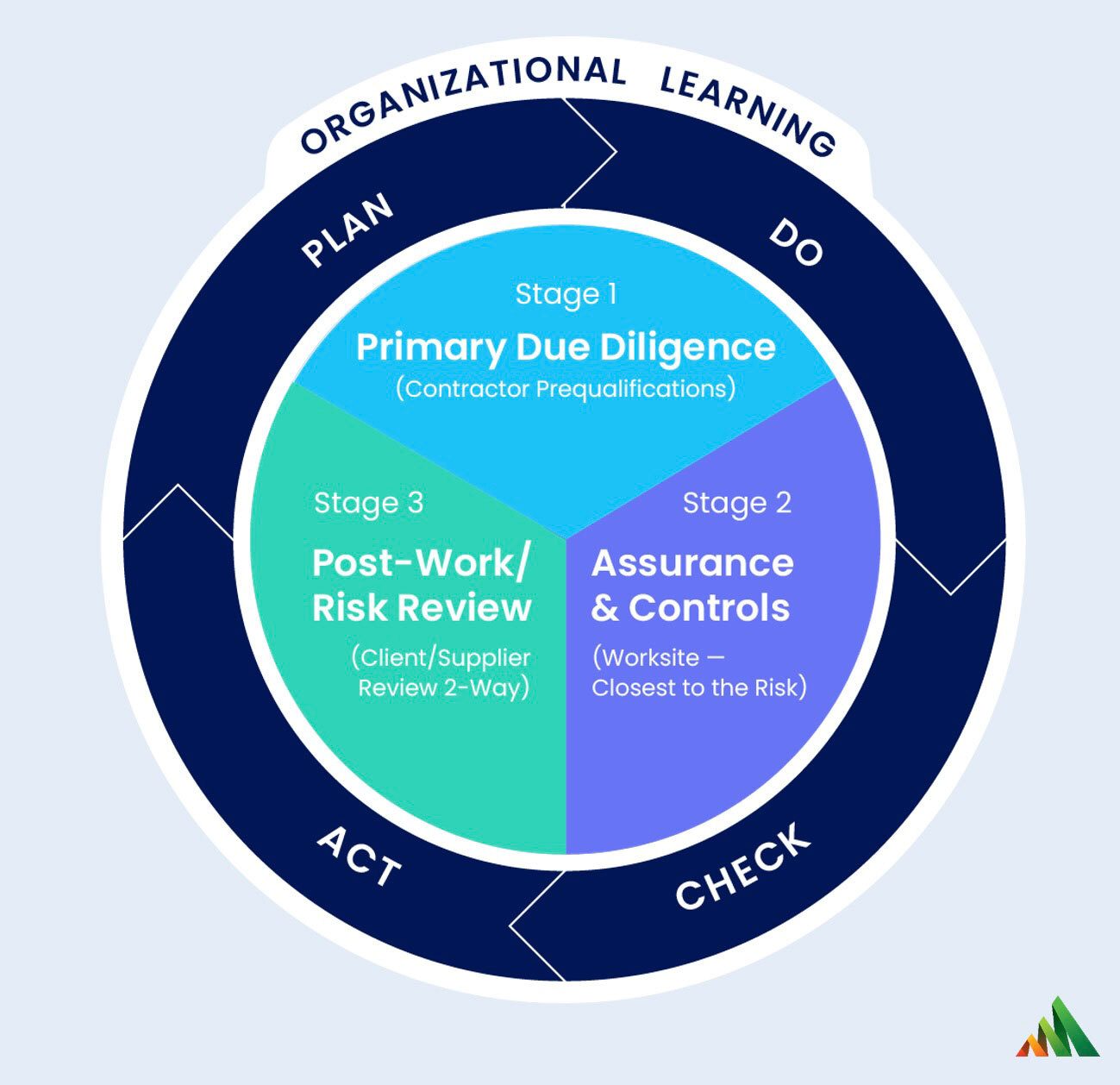

Graph: Avetta

What tells us risk is at an acceptable level?

Actively maintaining the “presence of safety,” rather than assuming risk is acceptable from merely looking at lagging indicator requires, requires a systems approach, such as the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) method found in safety management systems like ISO 45001 or ANSI Z10. This globally recognized method helps organizations build a cross-functional approach between stakeholders to:

Plan: Discuss the specific safety-creation activities that will be done (risk assessment, leader/worker engagements, serious risk review, corrective actions closed/risks removed, etc.) on a set cadence.

Do: Execute the planned activities, track them and capture for review. This includes prioritizing high-risk situations for immediate action.

Check: Verify if what has been done was effective, highlighting risks discovered and ensuring risks are controlled/acceptable.

Act: Leadership review, resourcing adjustments and information learned from the PDCA cycle is fed forward into the next planning cycle for continual improvement.

The goal is to build safety systems, build adaptability and resilience, as well as alert and visualize risks before they turn into incidents. Work systems that enable adaptability, monitoring and proactive inquiry through the PDCA process enable leaders to move from a reactive approach to a performance framework.

The real world of work is dynamic. Conditions shift, tools change, production pressures increase, resources decrease, and workers adapt to it all.

How are we improving?

This question forces organizations to look critically at their rate of learning and change. In fact, many are beginning to consider this a process of organizational learning. We need to ask: Are new insights being captured and applied through our PDCA process? How well are the ‘Planned’ safety activities, such as risk assessments and leader/worker safety engagements being received, and what are we learning? Is there measurable impact from prevention efforts alongside a review of incidents and injuries? And what has our process captured that informs other areas, such as audit, training and equipment operation to name just a few?

Creating a culture of improvement doesn’t require sweeping overhauls. Small, steady changes within a cycle of continual improvement and driven by feedback, data and frontline engagement can build compounding value.

A safety leadership compass: Navigating uncertainty with confidence

In a volatile regulatory environment, it’s tempting to assume that achieving compliance equates to performance improvement. It doesn’t. Asking the right questions that challenge assumptions, seek evidence and commit organizations to progress satisfy both due diligence while moving beyond compliance to establish a performance framework, where continually improving business processes and learning achieve the safety outcomes we all desire. Whether you’re an executive shaping strategy, an HSE professional leading change or an operations leader guiding teams, use these key points as your compass:

• Cl ose the gap between work as imagined and work as done.

• Measure what matters and focus on leading indicators that allow you to act early, before injuries occur. Minimize the use of lagging indicators, with the exception of Severity Based Lagging Indicators (SBLI)

• Continuously improve through a defined, systems-based approach such as PDCA.

• Safety leadership requires humility, curiosity and a systems framework to take us beyond the baseline of compliance. Leaders committed to these methods are finding that improvement comes from the most important of places, yet one that is easily overlooked: Where leaders and workers engage in a simple process of improving safety together.

Scott DeBow, CSP, ARM, currently serves as the Director of Health, Safety & Environmental for Avetta. With extensive experience in safety management, serious injury/fatality intervention strategy and risk-based learning, Scott plays a pivotal role in driving Avetta’s mission to create safe, secure and sustainable supply chains.