safety

LEADING

By Peter Furst

Issues occur within safety oversight

Separating safety management from operations isn’t always beneficial

n a prior article some of the problems with safety management were discussed from a historic and the program perspective (see Safety Management Challenges – Management and Practice Issues, published on July 25, 2022). Let us now look at a different source that potentially may create a situation which may also contribute to shortcomings in the effectiveness of the management of safety in construction field operations. Fundamentally some of this emanates from the industry’s reaction and response to the promulgation of the Occupational Safety and Health Act.

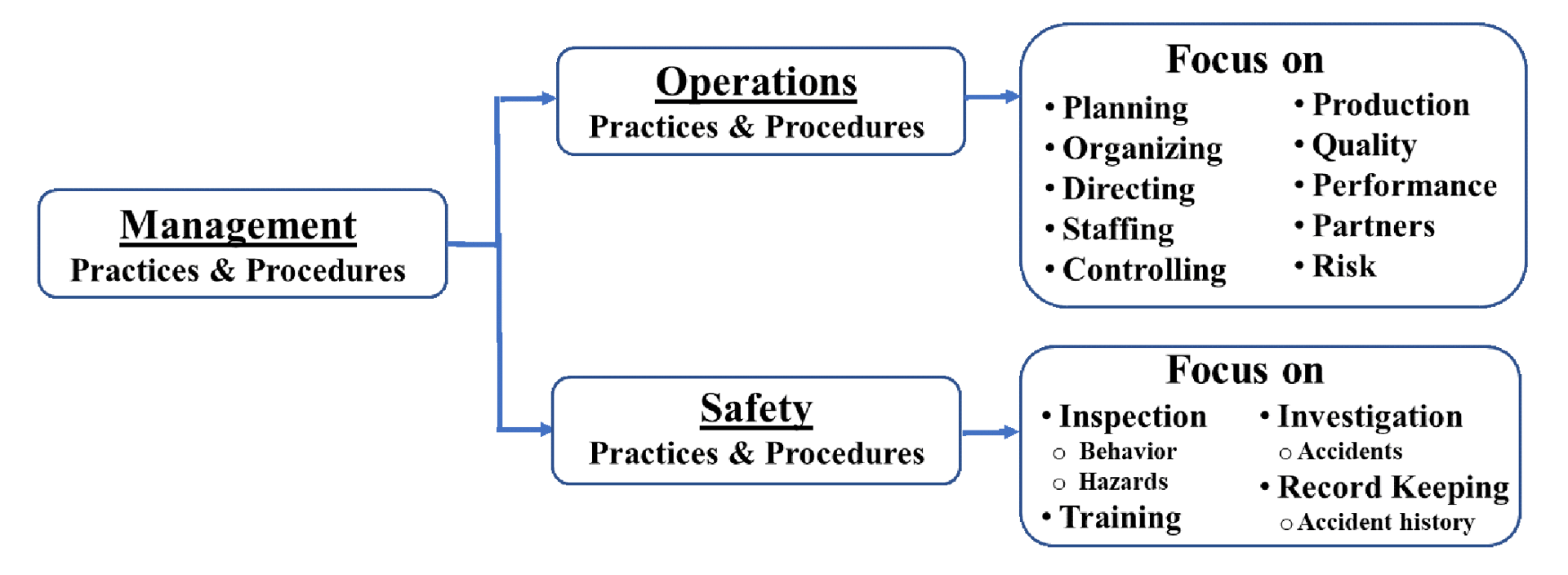

Due to the fact that the OSHA standards were voluminous, dealt with a large number of potential hazards conditions to which workers could be exposed while engaged in their tasks within the project work environment. Requiring a significant number of training session which had to be provided to the workforce in order to familiarize them with the standards, conducting site inspections as well as recordkeeping all of which required specialized knowledge, expertise and attention. Industry management made a determination that this would have to be handled by someone other than their field operational personnel and supervisors.

These construction supervisory staff and personnel were responsible for the field operations and production requiring planning, organizing, directing, staffing, decision-making, problem solving, expediting, and controlling the project delivery production work. This involved a large number of partners resulting in a complex supply chain as well as managing the risks associated with meeting contract obligations, and therefore should not have to take on the additional burden associated with the safety management requirements and responsibility.

I

Bifurcation of responsibility

This effectively segregated the oversight of safety from the organization’s field operations to be treated as a stand-alone function. The superintendent and the operational staff were primarily responsible for the production of the work utilizing the project schedule to manage the contractual obligation for the contract completion time and date. They had to ensure that the work was put in place in accordance with the design specification in order to meet the project quality expectations as well. On top of that they also had to manage any and all subcontractors to ensure that the project meeting or exceeding the contract obligations. So, the field staff took on a proactive operational role.

As a result, the organization assigned management of worker safety to a knowledgeable person or in some cases created a department to ensure that the organization was in full compliance with the requirements and obligation of the OSHA standards. This meant that the safety practitioner(s) became responsible to ensure that the physical condition where the workers were carrying out their work was free of physical hazards. The workforce was engaged in doing their work in accordance with the standards as well as ensuring that they performed their tasks in a safe manner and in a way that avoided getting involved in an accident and potentially suffering an injury.

Typically, the safety practitioner accomplishes this by making site visits (inspections) checking for hazardous conditions which are then either corrected on the spot or brought to the attention of the supervisor in order to have it corrected as soon as possible. The other aspect of the inspection tour was to observe workers working and looking for any action or behavior that was deemed unsafe and could result in an injury. Unsafe behavior or at-risk acts were then brought to the attention of the worker involved, the applicable OSHA standard reviewed and/or discussed as well as possibly a safer method then suggested so that the worker may proceed to work in a potentially “safer” manner.

The prescribed safety practices requires the collection of loss (accident) data and the posting of this record for a month so that employees working there may know of the company accident history as well as the submission of this losses data to the burau of labor statistics so that this information may be used to arrive at that industries annual loss experience, which was then made available to the public. This then became the standard metrics for safety management improvement practices in various industries. So, fundamentally safety management took on a potentially reactive role.

This data provides historic information of things that may have been done or occurred; conditions or situation that may have existed in the past. Since the future in not quite the same as the past such data or information may not provide very useful guidance in how to deal with the present problem or issue, or provide specific information on what changes should be made to operational processes, procedure or practices in order to improve safety outcomes going forward. For the identification of potential shortcoming in an going operational means and methods, different types of data and/or information is required which highlights the risk of potential negative consequences.

The functional separation of safety from operations also tends to focus the bulk of the safety practitioner’s improvement interventions on the worker in order to improve safety outcomes. The traditional interventions deployed have included possibly rewriting or modifying elements of the company safety program, training and/or retraining the workers on specific standards, emphasizing certain aspects of the program, making certain program elements or areas a discussion or training priority, greater emphasis placed on audits and inspections, as well as possibly implementing incentive programs, or putting greater emphasis on disciplinary measures. These interventions’ improvement works to some extent, but eventually their effect "plateaus," and more importantly they almost never achieve lasting long-term improved results, because they really do not address the underlying factors or adverse situations that lead to the negative consequences.

The functional separation of safety from operations also tends to focus the bulk of the safety practitioner’s improvement interventions on the worker in order to improve safety outcomes.

Source of the risk of injury

It is a fact that construction is an industry in which workers suffer more accidents that result in injuries and/or fatalities than many of the others. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, workers suffer thousands of injuries and hundreds of fatalities on construction sites annually. The risks of injury at work could be attributed to:

• Bad luck.

• The physical work environment being unsafe - hazardous conditions.

• Some deficient act or unsafe behavior on the part of the worker.

• Risk due to shortcomings in the operational means & methods selected and/or used.

Let us address bad luck. This means that no one could have done anything in order to avoid having the unfortunate event occurring with their resulting adverse outcome. That is rather difficult to accept. In the previous article on Safety Management Challenges – History & Program Issues, we discussed two major studies of accidents. In the second one Frank Bird reviewed over 1,700,000 accidents and he found that about ninety five percent were attributable to employee action and about five percent were attributable to physical conditions. There were no accidents attributed to bad luck.

The existence of hazardous physical conditions and their prevalence will vary depending on the industry, the nature of the project, type or work, and more specifically the things project staff may have planned or done to address these potential hazards or risks associated with the envision tasks to be performed. Construction is a case in point. A building or structure under construction may possibly change its configuration or its physical condition on a daily basis because of new work being put in place. This may create situations where the physical state of the work may be hazardous to someone working in and/or around it as well as possibly traversing that area. The people responsible to oversee the project should address any such potentials when they plan the work, select the means and methods, make the task assignments, set production goals, and the list goes on.

Conclusion

As we discussed in the previous article, since OSHA standards are primarily focused on worksite conditions then such exposures can, and should be identified as well as addressed before any worker is assigned or exposed to them. The problem is that such hazards may be the result of supervision’s plans, selected means and methods, task assignment or just a function of the work as it progresses.

Another important factor is the fact that the safety practitioner may visit the job once a week or possibly once a month. So, if this person is to find and address such hazardous physical exposure, or unsafe behavior, workers would be exposed during dose times. This would indicate that the safety practitioner would have to be on site just about all the time, which is or may be impractical. Which would strongly suggest that the project staff ought to pay attention to such potential risks’ which may possibly be an integral part of their selected means and methods.

We will address in future articles, point 3 and 4 above as well as other possible factors that could and should be addressed during operational planning in order to more effectively address occupational hazards, and the management of risks which may potentially cause accidents and injuries. This would point to the possibility of restructuring the bifurcated approach to operations and safety as well as devise a more holistic and integrated project delivery process.

Peter G. Furst, MBA, Registered Architect, CSP, ARM, REA, CRIS, CSI, is a consultant, author, motivational speaker, and university lecturer at UC Berkeley. He is the president of The Furst Group which is an Organizational, Operational & Human Performance Consultancy. He has over 20 years of experience consulting with a variety of firms, including architects, engineers, construction, service, retail, manufacturing and insurance organizations. He has guided organizational systems integration, aligning business and operational goals, enhanced management’s leadership and operational execution, utilizing Six Sigma, lean and balanced scorecard metrics optimizing human and business performance and reliability. Send questions and comments to peter.furst@gmail.com